Figure 2: Artist's conception of how Solar-B (now called Hinode, japanese for "sunrise") might look in orbit. Now that it's launched, of course, nobody knows what it looks like!

The most recent and most powerful solar observatory in space - Hinode - has recently been launched by JAXA on its last M-V (Mu-5) rocket. Remarkably, Hinode carries the very first high-resolution telescope into space to study the Sun at optical wavelengths, i.e. in the photosphere and chromosphere. This telescope,SOT, is totally free of the bane of all astronomers viewing the sky through the atmosphere, seeing.

Launched in October 2006, Hinode is initially observing during solar minimum. But it is well-equipped to observe solar flares with the combination of SOT and the X-ray Telescope (XRT), a full-disk X-ray telescope which is a follow-on to the earlier ISAS solar observatory Yohkoh SXT instrument. Thus it is a new departure rather than a successor to Yohkoh, the earlier ISAS solar observatory. Hinode's brilliant new observations of the photosphere and lower solar atmosphere (in particular) promise to tell us many important things about the processes that lead to and follow from flares. In particular the optical telescope, SOT, can observe in the Fraunhofer H-line of calcium, a strong chromospheric line.

The unexpected did happen, as though on schedule, when in December 2006 the Sun produced a last gasp (probably) of major activity before the true minimum. This Nugget describes observations of an X-class flare of December 13, 2006, which was also observed by RHESSI - in principle, an ideal complementarity.

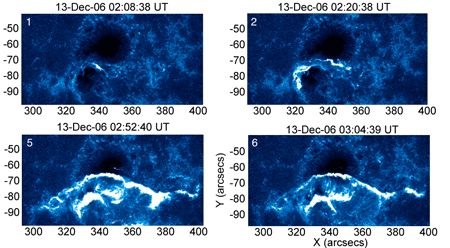

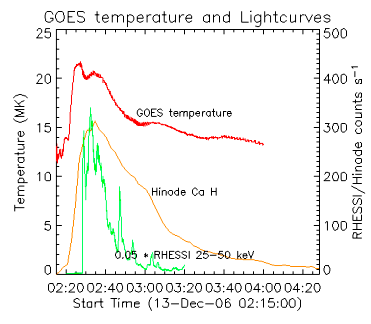

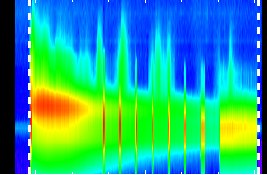

The figure below shows the time series of the flare development, including hard X-rays (from RHESSI). The Hinode H line has a smooth time profile, suggesting a "thermal" excitation rather than a nonthermal one, as represented by the RHESSI hard X-rays. This is immediately interesting because of the small number of flare observations in this line.

With regards to RHESSI, we have apparently excellent observations (see Figure 3) but sadly, it turns out, they are only spectroscopic. This flare, among all flares, chose to occur just at the center of RHESSI's rotation (see this nugget for some further explanation). For technical reasons this means that imaging is very difficult. The Hinode chromospheric (H-line) and photospheric (G-band) images show remarkbly fine structures, and we have thereby lost a chance to make a detailed comparison at the highest resolution. However, analysis of this great event is just beginning, and we can hope for more sophisticated analyses than has been reported here.